¶ Introduction

The magnetic moment is a fundamental quantity that characterizes the magnetic field produced by a current distribution. It is the magnetic analog of the electric dipole moment and plays a central role in understanding magnetic materials, current loops, atomic structure, and astrophysical magnetism.

In classical electrodynamics, the magnetic moment arises naturally when calculating the vector potential of a localized steady current distribution in the far-field limit. The first non-zero term of the multipole expansion is the magnetic dipole moment.

¶ Setup

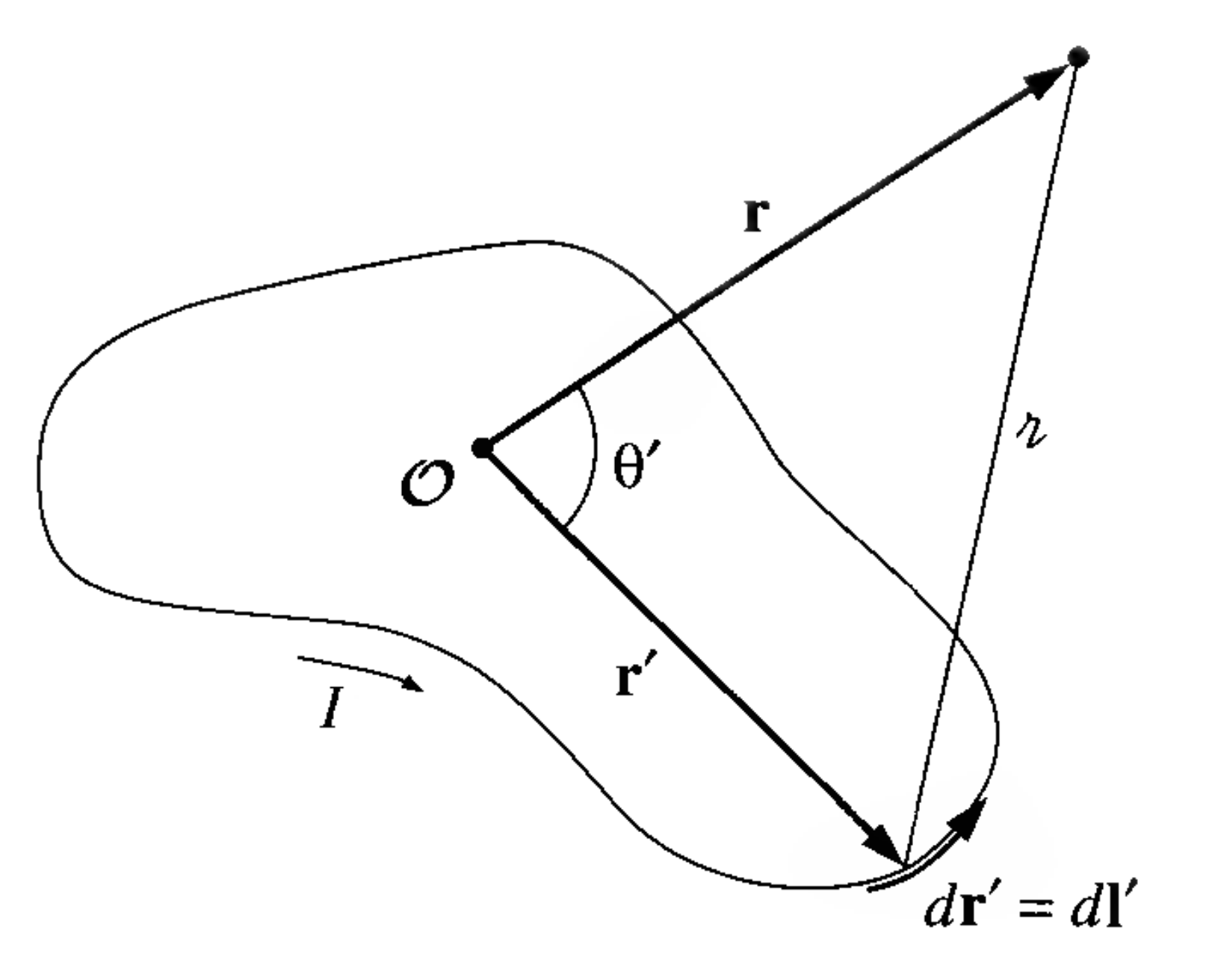

We begin with the expression for the vector potential generated by a steady current distribution :

Assume that the current is localized within some finite region around the origin, and we are interested in the potential far away from the source, so that , where is the distance from the origin to a point where we are measuring the potential, and where is the distance between the origin and a point in the current distribution.

To make things easier, let's assume our current distribution is a steady current running through a wire as shown in the diagram. Then , where is the 1-dimensional current vector, so that we only have to integrate over the wire instead of a volume :

where we also take advantage of the constant current condition ()

¶ Derivation

Since , we can expand the denominator of the integrad using a multipole expansion, which tells us that it can be expanded as

where are the Legendre polonomials. Thus, the vector potential becomes:

Or more explicitly,

Now, it happens that the magnetic monopole term is always zero, for the integral is just the total vector displacement around a closed loop:

This reflects the fact that there are no magnetic monopoles in nature. Thus, in the absence of any monopole contribution, the dominant term is the dipole (except in the rare case where it, too, vanishes):

This integral can be rewritten in a more illuminating way if we invoke a vector calculus identity for vector areas:

so that the dipole term can then be written as

where is the magnetic dipole moment:

Here is the “vector area” of the loop.

¶ Torque on a Current Loop

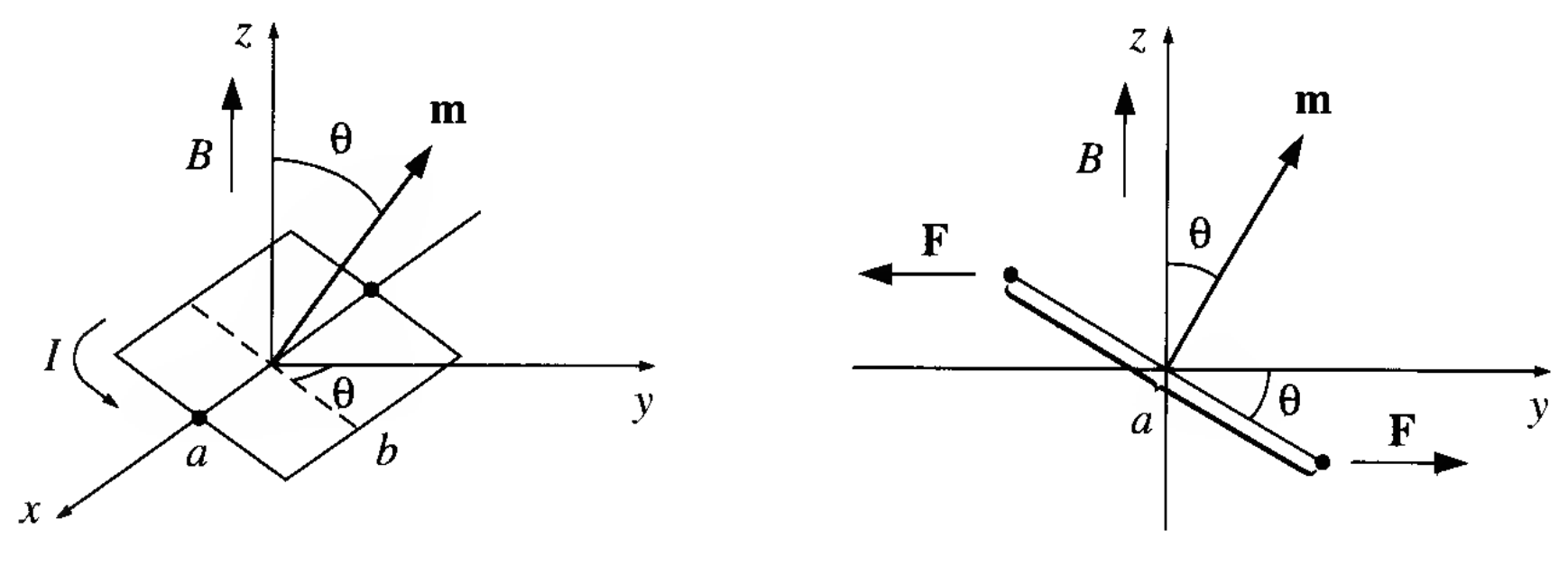

Consider a square loop of side lengths and , carrying a steady current . Center the loop at the origin, and tilt it an angle from the axis towards the axis. Let point in the direction. The forces on the two sloping sides cancel (they tend to stretch the loop, but they don’t rotate it). The forces on the “horizontal” sides are likewise equal and opposite (so the net force on the loop is zero), but they do generate a torque:

The magnitude of the force on each of these segments is

and therefore,

Or more compactly,

where is the magnetic dipole moment of the loop. This equation gives the exact torque on any localized current distribution, in the presence of a uniform field; in a nonuniform field it is the exact torque (about the center) for a perfect dipole of infinitesimal

size.

This torque tends to align the dipole moment vector with the magnetic field , just as an electric dipole tends to align with an electric field.

¶ Energy of a Magnetic Dipole in a Magnetic Field

As we’ve already seen, the torque on a magnetic dipole placed in an external magnetic field is:

This torque tends to rotate the dipole so that it aligns with the magnetic field direction — just like how an electric dipole aligns in an electric field.

To rotate the dipole quasi-statically from one orientation to another, work must be done against the torque. Let be the angle between the vectors and . The magnitude of the torque is:

The infinitesimal work required to rotate the dipole by an angle (against the torque) is:

The potential energy difference between two orientations is the negative of the work done by the torque:

Choose as the reference orientation (where for convenience). Then:

Thus, we obtain:

And since , we can express this more compactly as:

This expression tells us:

- The energy is minimized when is aligned with .

- The dipole is in a stable equilibrium when .

- The dipole is in an unstable equilibrium when or .

¶ Force on Magnetic Dipole

We already know the potential energy of a magnetic dipole in an external magnetic field is:

This energy is position-dependent when varies in space.

In mechanics, the force associated with a potential energy function is:

Substitute the expression for :

So we obtain immediately:

This is the total force on a magnetic dipole in a non-uniform magnetic field.

You might wonder: is this legitimate, given that magnetic forces do no work on moving charges?

Yes — because the work done by the magnetic field on the whole dipole comes from the torque rotating the loop, not from translating it. But if varies with position, then changes as the dipole moves, and a force is implied by this changing potential.

This derivation works exactly because we’re treating as a rigid dipole, and only considering external work needed to move it through a spatially varying .

¶ Magnetic Moment of Individual Particles

Although the magnetic moment is often introduced in the context of macroscopic current loops, it also arises at the microscopic scale as a fundamental property of particles with angular momentum. In classical and quantum physics alike, magnetic moments couple to external fields via:

¶ Classical Model: Orbiting or Rotating Charge

In classical electrodynamics, a particle of charge moving in a circular orbit of radius and angular frequency constitutes a current:

The magnetic moment associated with this circulating current is:

where is perpendicular to the plane of the orbit.

The angular momentum of the particle is:

So the magnetic moment is related to the angular momentum by:

This ratio is called the gyromagnetic ratio, denoted for orbital motion. Note this result arises entirely from classical physics.

¶ Quantum Orbital Magnetic Moment

In quantum mechanics, the orbital angular momentum of an electron leads to a magnetic moment of:

- This is structurally identical to the classical formula.

- The negative sign reflects the negative charge of the electron.

The natural unit of magnetic moment in atomic physics is the Bohr magneton:

Thus, we often write:

¶ Spin Magnetic Moment

Unlike orbital motion, spin has no classical analog — it is an intrinsic property of quantum particles. However, it also carries a magnetic moment. For an electron with spin , Dirac theory predicts:

- Here, is the Landé g-factor, which equals 2 exactly in Dirac theory for a free electron.

- Quantum electrodynamics predicts a small correction: (Jackson §5.7).

In terms of the Bohr magneton:

¶ Magnetic Moments of the Proton and Neutron

Despite its charge neutrality, the neutron has a measurable magnetic moment due to its internal quark structure (Jackson §5.7). In nuclear physics, the magnetic moment is measured in units of the nuclear magneton:

which is analogous to the Bohr magneton but scaled by the proton mass.

Empirical values:

- Proton:

- Neutron:

These values cannot be explained by point-particle models and are evidence for non-pointlike internal structure — specifically, the dynamics of constituent quarks.

¶ Summary Table

| Quantity | Formula | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Classical current loop | \vec{m} = I \vec | Griffiths §5.4.1 |

| Classical gyromagnetic ratio | \vec{m} = \dfrac{q}{2m} \vec | Griffiths §5.4.1 |

| Quantum orbital moment | \vec{m}_\text{orb} = -\dfrac{e}{2m_e} \vec | Griffiths QM §4.5 |

| Spin magnetic moment | \vec{m}_\text{spin} = -g \dfrac{e}{2m_e} \vec | Griffiths QM §4.5, Jackson §5.7 |

| Bohr magneton | \mu_B = \dfrac{e\hbar} | Standard definition |

| Nuclear magneton | \mu_N = \dfrac{e\hbar} | Jackson §5.7 |

| Proton moment | Empirical | |

| Neutron moment | Empirical |

Magnetic moments of particles are crucial in:

- Atomic physics: Zeeman splitting, fine structure

- Quantum spin dynamics: precession, spin resonance

- Nuclear physics: NMR, nuclear structure

- Astrophysics: synchrotron radiation, magnetars

- Fundamental tests: -factor precision confirms QED

Although the origin of varies (orbital vs. spin vs. internal structure), its coupling to external fields is always through:

¶ Summary

The magnetic dipole moment captures the leading-order behavior of localized current distributions in the far-field, analogous to the electric dipole moment in electrostatics. It arises naturally in the multipole expansion of the vector potential , and plays a central role in describing the interaction between currents and magnetic fields.

Key results:

-

Definition:

where is the vector area enclosed by the current loop.

-

Vector potential of a magnetic dipole (dipole term in far-field):

This approximation holds when , i.e., far from the current distribution.

-

Torque on a magnetic dipole in a magnetic field:

The dipole tends to align with the field, just like an electric dipole in .

-

Potential energy of a magnetic dipole in a magnetic field:

Energy is minimized when aligns with .

-

Force on a magnetic dipole in a non-uniform magnetic field:

This force moves the dipole toward regions where the magnetic field is stronger along the direction of .

These expressions are valid in the dipole approximation, when the magnetic field does not vary appreciably across the spatial extent of the current loop. They are foundational to topics ranging from magnetic materials and NMR to astrophysical magnetospheres and magnetically-driven winds.